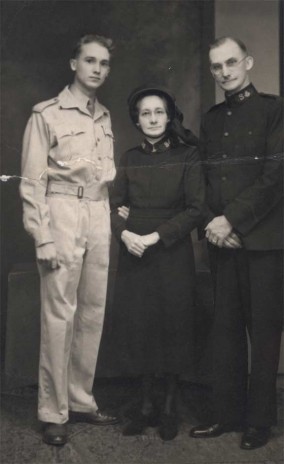

Cecil Skotnes was born in 1926, the son of missionaries. Edwin Eilertson and Florence Kendall had married and taken the name Skotnes from Edwin’s home farm in Norway. As officers in the Salvation Army they travelled to Canada and then to Africa where they worked in Mozambique, eventually finding their way to East London where Cecil was born. At first they thought to call him Stanley Livingston, but decided in favour of Cecil Edwin Frans Eilertson Skotnes. He was their fourth child and the last to survive to adulthood. His sisters were Olive Jean Maple Leaf and Dorothy Ivy and his brother was Arthur. Nine years later they left the Eastern Cape, stopping for a time in Kroonstad and then settling on the reef.

Cecil Skotnes was born in 1926, the son of missionaries. Edwin Eilertson and Florence Kendall had married and taken the name Skotnes from Edwin’s home farm in Norway. As officers in the Salvation Army they travelled to Canada and then to Africa where they worked in Mozambique, eventually finding their way to East London where Cecil was born. At first they thought to call him Stanley Livingston, but decided in favour of Cecil Edwin Frans Eilertson Skotnes. He was their fourth child and the last to survive to adulthood. His sisters were Olive Jean Maple Leaf and Dorothy Ivy and his brother was Arthur. Nine years later they left the Eastern Cape, stopping for a time in Kroonstad and then settling on the reef.

In Johannesburg they lived in Loveday Street, then a sprawling estate with a tennis court gone to seed and dry grass and bleak ground beyond. He went to school on a tram, barefoot more often than not, playing out in the veld in the afternoons and running down to the rivers to fish. The depression never really affected his family – as missionaries they had virtually nothing anyway, and he remembered his childhood as carefree and happy. At school, a woodworking teacher, Johan Couzyn who had been an assistant to Anton van Wouw and a friend of Eugene Marais, got him to make a sculpture – as it turned out a portrait of a Bushman, and it was given to the director of education when he visited the school. Here he also met his long time friend, Leon Rubens, and enjoyed playing rugby and riding the crazy horse at sideshows.

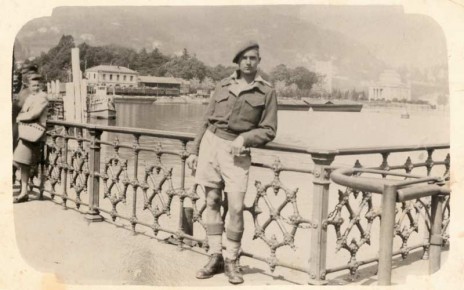

Cecil at lake Como

When he turned 17 he grabbed the opportunity to leave school and join the South African Artillery, serving in Egypt and Italy and spending several months in Florence which was to become one his favourite places in the world. The war was a period of adventure and the broadening of horizons. In Florence he befriended an Austrian writer whose brother Heinrich Steiner was a painter who gave him his first serious art lessons. It was the time of the unpacking of the city – Michaelangelo’s David had been packed up during the conflict and he watched the bricks being tapped off, the sand falling away to reveal its great head. It was late evening and the city was intoxicatingly lovely. Here too he saw the work of Masaccio, Giotto and Donatello – artists whose work was to become a major inspiration to him. Europe was, however, starkly contrasting to Africa. Colour and shape was different as was the experience of time and place. In Europe history is, in one sense, constantly on display; in South Africa, much is hidden beneath the surface. In Europe there is a sense of human closeness, even claustrophobia; in South Africa space is almost endless. In Europe he was fascinated by this closeness, by the rich heritage of the Renaissance, by Greek mythology and Greek and Roman architecture and art. Later in Africa he would be nourished by the space, its harshness and its sense of wild mystery.

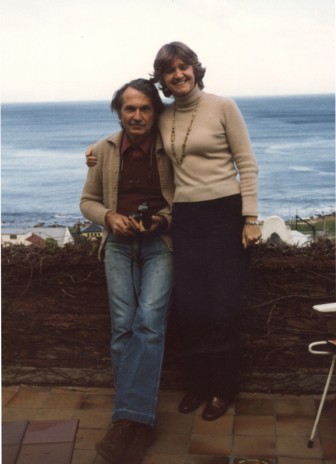

Cecil & Thelma

He returned to Johannesburg and completed his Matric through correspondence joining Wits to study for a Fine Art Degree. Maria Stein Lessing, who taught art history and had a rich understanding of African arts, made a significant impression on him, and it was here he encountered Larry Scully, Christo Coetzee, Esme Berman and Nell Erasmus amongst others. During this time Cecil met Thelma, a lovely, vivacious woman, ex-convent girl with a nineteen inch waist who had flair, deep intelligence and incomparable warmth, and was daring enough to marry a man who wanted to be an artist with no sure prospects, and keep the home fires burning. They married, honeymooned briefly at the Mount Nelson before travelling to London where they stayed for nine months. Thelma worked for a television company and Cecil washed dishes at Jo Lyons visiting the British Museum during time out. Again, Europe was to have a profound influence on him through the experience of the Egyptian, Assyrian and pre-classical Greek art that he saw in places such as the British Museum. It was, however, the colonial collections from Africa that were to have the greater impact. Cecil may well have stayed in Europe were it not for this, but instead he was drawn back to Africa, and like his father many years before him he made South Africa his permanent home.

After the young couple returned home to Johannesburg, Cecil took a job as an assistant to the superintendent in the Non-European Affairs department. He was sent to work in the townships. At that time there was no Soweto – it was Jabavu and Orlando 1 and 2, and beyond that was a swampland with game birds and Iron Age ruins. It was only later, after seeing other Iron Age remains, that he realised the extent of what was there, and what is now buried under Soweto. After this he was asked to take over Polly Street, a recreation centre, to head both art and music activities. At the time it bordered the so-called Bantu Sports Ground. He remembered it as follows:

“The back wall of it was a great place for Mafia activities. There was a field which was pitted with holes like a rabbit warren, holes big enough to take a four gallon can in which the skokiaan queens made their brew. On Friday nights the brew was sold. They used to build a great fire there. One saw incredible sights silhouetted against the firelight … five or six hundred people. And of course if it got riotous the only place where anyone trying to run could find any haven was on the steps of the centre. … Many times on a Sunday or Monday morning we washed the blood off the steps. …” (Interview with James Ambrose Brown)

It was here that the bouncer at Polly Street, boxer Ezekial Dlamini, known as King Kong killed his girlfriend, leaving Cecil to call the police to take the body away. The jazz musical that was later created about Dlamini’s story, now famous as the first that transgressed apartheid divisions, was a rich expression of the vibrancy of life at that time and we would sing the songs together at home, mostly out of tune. Cecil could often be heard humming the theme song.

When Cecil came to Polly Street it had all but closed, everything had come to a standstill. There was one student, apparently, but he drowned within a month of his arrival. Cecil began to advertise. It had been a recreational centre but he decided it should become an artschool. He advertised in Drum Magazine, on the African radio stations and in the township newspaper. Few students came. Then he got Thrups to donate chicken soup that was served during classes. Students began to flock to the centre and soon he was teaching up to 75 per week. It became a refuge and the only art school for blacks in the country. Students arrived in strange ways. One night a young man came running into the centre, the police in hot pursuit. Cecil sat him down, gave him an apron and pencils and instructed him to draw the still life in front of him. As it turned out he had ability, and became a regular.

Word of the centre spread and early on some of the great talents of that decade came to study. Sydney Kumalo and Ephraim Ngatane were among them. In addition to teaching classes Cecil tried to find ways to develop a sense of professionalism amongst his proteges, and it is here that his work as an artist and teacher/advocate of black art in South Africa came together in interesting ways. While it is true that as an artist the landscape and the figure within it has been Cecil’s abiding theme, it has not been the only one to absorb his creative mind. Being raised in the home of missionaries and with an enduring love for Catholic Italy, Cecil has had a greater than average exposure to the traditions of the Church. It was to the church that Cecil first looked to expose his more talented students to the opportunities of the professional artist. The first significant commission Skotnes secured was for Sydney Kumalo (later to become a well known and highly respected artist) who, along with other Polly Street students and Cecil’s help, decorated the Catholic Church of Kroonstad. Other commissions to make sculptures and stations of the cross for various churches followed, and soon a growing number of black artist were making and marketing their work. The ripple effect was profound. Skotnes arranged for more commissions and exhibitions to take place and by the 1960s many galleries were actively seeking the work of black artists. By the time the apartheid authorities effectively shut down Polly Street (such a thriving centre could not be tolerated in a “white” area), there was a prosperous community of black artists.

The Polly Street project was to have a profound effect on all involved. Later in the 1980s Cecil was quoted as saying: “Whatever achievements have been registered by black artists are monuments to their natural ability and their desire to create are in the face of the most astonishing difficulties. Technical training has almost been totally denied the aspirant black artists and financial support for their efforts has been negligible. It has been a privilege for me to have been associated with so many artists from these townships from whom I have learned so much, not only artistically but about the meaning of dedication.”

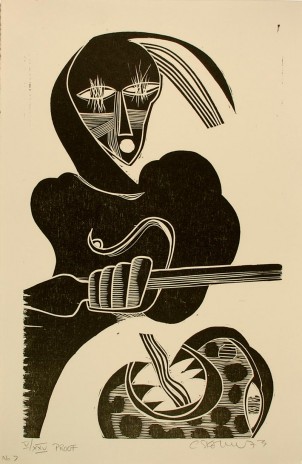

In the 1960s Cecil Skotnes’s career was to really take off. Initially he painted but was soon encouraged by a friend, the master goldsmith and art collector Egon Guenther to try woodcutting. It proved to be a perfect medium for him. His early woodcuts were of landscapes, influenced by the work of Willie Baumeister and Rudolph Sharpf, but his contrasting experiences of the European and the African landscape drove him to try to develop a genre and a style that was uniquely South African. This challenge was not only iconographical, it was formal too, and the medium of woodcutting offered Cecil the possibility of finding new form for the symbolism he increasingly began to attach to a particularly local vision. Though Cecil was later to return to painting, woodcutting and engraving has been an enduringly loved medium. In later years he used it less for land and figure-scapes than as a medium for narrative, and it was in colour woodcut that he produced ground-breaking portfolios of image and text around the themes of neglected South African histories.

From the Shaka portfolio

Cecil’s early use of the medium of woodcutting soon translated into a focus on the block itself. Instead of cutting the block and then using it as a means to an end – the print – he began to colour and shape the blocks, using them as a surface for paint and dry pigment. He also began to work in mural, using a technique of coloured cement laid into lime plaster which he would then engrave away exposing layers of colour and incised lines. He carried out many public commissions in this medium.

Along with the changes in process and technique, came a shift from an interest in the landscape and the figure within the landscape, to a concern with some of the powerful narratives of South African history. One of these was the story, still relatively unknown amongst non-Zulu speaking South Africans, of the great Zulu king Shaka who was assassinated in 1828. It had served the purposes of the apartheid government to suppress African histories, or tell them in such a way as to cast them as barbaric or savage. Skotnes’ work around the story of Shaka showed, by contrast, a heroic figure, comparable to the great heroes of classical Greece and his depictions of the figure of Shaka contributed to shifting public attitudes to the role of the great nation states in pre-colonial South Africa.

Sculptures in the Skotnes family home

Cross cultural connections were, for Skotnes, lived experiences. In the home he made with Thelma and his children John and Pippa, Persian carpets, European sculpture, oriental ceramics, African fabrics, were bartered or bought, or received as gifts. It was a space of cultural mobility. Sangomas threw bones on the Afshar, artists arrived with their portfolios under their arms, friends came for lunches and suppers and at night, at times, the police would arrive to check on infringements of the Group Areas Act. Exhibition openings were big events. Everyone dressed up and the press would publish reviews the very next day, sometimes on the front page of the paper. Cecil and Thelma travelled a lot, and when the Salvation Army grandparents came to stay to look after the children, the African sculptures would be dressed in paper outfits to hide their shameful nudity.

In the late 1970s Cecil moved from the highveld to Cape Town. This represented a radical shift in environment and a move to a more contemplative way of interacting with the landscape. The Cape is suffused with blues and violets, the light is softer, more influenced by rolling cloud banks that drift in from the north west, and the greys and greens of the sea. At this time he made a series of landscapes influenced by the ocean and at the same time he recalled the landscapes he had visited in earlier years. Included in these were the memories of the Brandberg, a great mountain which rises out of the Namib desert and which was the home of aboriginal hunter-gatherers who left their own paintings on its rock surfaces many thousands of years ago. In these works Cecil reaffirmed that ours is a landscape not only full of the colour and heat and light of Africa, but a landscape full of history and memory – places most alive to the human drama they have witnessed.

Through all these years Cecil Skotnes has been as well known as a teacher and mentor as he has as an artist. If one could single out the most outstanding influence his parents’ lives had on him, then it is surely this: the value of one’s achievements can be measured in the things that one leaves behind. For Cecil, this is to be understood not only as one’s material effects—in his case a huge corpus of work which has contributed to the global imaginary, and to the way in which South Africans perceive their own creative heritage—but also in the way in which one is able to change the lives of others for the better. For Cecil, his lifelong mission has been to nurture talent and encourage creativity, particularly in places where the apartheid government had deliberately excluded this possibility. The effect of this has been a major contribution to the diversity of South African art.

In his later years, Cecil Skotnes began to reflect more on his own origins. The journey of his father from Norway to Canada and then to Africa, the death of his uncle on the Sptizbergen, the cold dim landscape of the Arctic circle and its contrast to the heat of the South African highveld, and the damp richness of the Cape coast. He produced works on these themes, most notably two portraits of the dead uncle, a trapper who was found, frozen in his hut in the company of the bears, foxes and birds he had hunted. But his last works were about none of these things in particular, yet about all of them in general. In some of his last engraved paintings can be discerned the shadows of the painted altarpieces of the Renaissance, of lost kingdoms and of ruined cities of the Mediterranean. These pictures hold the memories of the gold masks of Mycaena, the bronze figures of Delphi, the stained pottery and the carved sticks of the early agriculturalists of eastern Africa. In their line and gestures, they lament the lives lost, the sacrifice and cruelty and the potential not realised by the miserable system of separate development that held South Africa in its grip for half a century. Above all they celebrate art as the realisation of the most valuable of human all human experiences and the one that should be most accessible to everyone – the imagination.

Cecil Skotnes died on the 4th of April 2009. He had created for himself and those dear to him a wonderful world rich with art, with colour, with music and poetry, with a majestic sense of history with the reciprocal generosity of friendships, with astonishing selflessness and kindness and with humour and courage and an unwillingness to ever take a grim view of things, but for injustice.

Cecil Skotnes’s career has been a rich and rewarding one from which many have benefited – his family, his students, young artists, his friends and those who have bought and bartered his work. His contribution has been recognised by all those who love him and his art, by universities who have conferred honorary degrees on him (UCT, Wits and Rhodes) and by the State President with the award of the Order of Ikhamanga in gold for service to the country and, in particular, for his contribution to the de-racialision of South African art.

Pippa Skotnes 2009