Beginnings

Joan Couzyn was my first art master, and during the very early years he taught me those essentials which are so much the basis of his own art – honesty, a love and understanding of materials, and dedication.1

Cecil Skotnes was born on 1 June 1926 in East London, the youngest of four children. His Norwegian father, Edwin Andor Skotnes, was an ordained Lutheran minister and missionary, but after his marriage to Florence Kendell, a Canadian and an active member of the Salvation Army, he, too, joined that organisation and devoted the rest of his life to social work among the needy. In time Cecil grew very close to his father and as a result he, like the older man, developed an intense interest in history, particularly ancient history. During Cecil’s adolescence his father was superintendent of a hostel for young men in Johannesburg. Since the Skotnes family had living quarters at the hostel, and often shared their meals with the inmates who came from various social and religious backgrounds, Cecil learnt that before God all people are equal. He attributes his interest in social upliftment, to which he unceasingly contributes in various ways, to this early background and his parents’ example.

Cecil enjoyed drawing and painting. Even while he was at Twist Street Primary School in Johannesburg he said that he was going to become an artist. During his first term at Con Cowan Junior High School the woodwork master, Joan Couzyn, a sculptor of considerable merit, observed the boy’s skill at drawing and decided to take him off the customary woodwork classes. He taught him modelling instead and Cecil’s career as an artist was on its way.

When Skotnes left school his father secured a place for him in a mechanical draughtsman’s office where he worked for about eight months. He claims that the experience gained there prepared him for the technical aspects of the large architectural commissions he was to carry out years later. In 1944 he left the office to join the army.

While his regiment was stationed in Milan after the Italian campaign, Skotnes went to Santa Maria della Gracie to see Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper. The visit was to be an almost mystical experience. When he arrived at the site of the monastery he found only one wall of the refectory standing, bolstered by sandbags to protect the famous painting that had miraculously survived the bombing of the city. This scene, and the wonder that the painting was saved, remained imprinted on his mind. He vowed he would come back to see the great work, and it was at that time that the dream to create a Last Supper himself was born.

In May 1945 Skotnes went on leave to Florence where he stayed until November. During this time he made watercolours and drawings, usually scenes along the south bank of the Arno which had been partially destroyed by the enemy. He met an Austrian artist, Heinrich Steiner, who had lived in the city for many years. They would come together to discuss art, and not infrequently the older man criticised the aspirant artist’s sketches, giving him valuable professional advice. Together they looked at and discussed the great art of the Renaissance. Skotnes felt particularly drawn to the work of Giotto, Donatello and Masaccio, artists whose austerity was akin to his own, and whose titanic figures were to serve as inspiration, and much later, as prototype, for his art.

Towards the end of 1945 the South African soldiers in Italy were translocated to Egypt to await transport home. During that time Skotnes attended formal classes at an art school in Cairo, but after meeting compatriot Gordon Vorster, who was in charge of the Helwan Art School, he left Cairo to supervise the smaller school in Vorster’s place. The South Africans returned home in mid-1946. To fill the time before becoming a full-time student Skotnes went back to work in the draughtsman’s office where he had been employed before he joined the army. Simultaneously he attended classes part-time at the Johannesburg Technical College Art School.

In 1947 he enrolled as an art student at the University of the Witwatersrand. The course in the fledgling Fine Arts Department was limited to painting (in watercolours and oils only), drawing (including ‘geometrical drawing’ to instil, it was believed, some professional discipline) and history of art. Graphic art was not part of the Wits curriculum, and, to underscore this limitation, Skotnes maintains that the word ‘woodcut’ was not even mentioned during his years at art school.

Among his fellow students were Larry Scully and Gordon Vorster (both, like Skotnes, ex-servicemen), Christo Coetzee and Nel Erasmus (all to become prominent artists and subsequently referred to as ‘The Wits Group’) and Esmé Berman, who became the first art historian to chronicle South African art comprehensively. Of their teachers, Willem de Sanderes Hendrikz, the sculptor who taught drawing, and Maria Stein-Lessing, the art historian, meant the most to Skotnes. In time he was to collaborate with Hendrikz on sculpture projects, and they remained friends until the sculptor’s death in 1959.

Maria Stein-Lessing was perhaps of even greater importance in Skotnes’ aesthetic and intellectual development. In the parochial setting of the Wits art school Dr Stein-Lessing, a Prussian Jewish refugee, stood out as an erudite art historian, unique in South Africa at the time. She was dynamic and eccentric. This kept her students spellbound and it inspired them to study, drawing their attention to fields of artistic endeavour that had been entirely unknown to them. Not only was she well informed on European art, especially that of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, she was also conversant with and infectiously enthusiastic about twentieth-century developments. It was she who first introduced Skotnes to German Expressionism, which was later to inspire him considerably. She had, too, a wide-ranging knowledge of, and an insatiable curiosity about, African art. As a sideline to her teaching. Dr SteinLessing ran a small business, called L’ Afrique, dealing in African arts and crafts in downtown Johannesburg. This was like a magnet for her students. They often went there to browse and, inevitably, to indulge in stimulating conversation with their mentor who became their fiercely loyal friend.2

After completing the course for a BA Fine Arts Degree in 1950, Skotnes married Thelma Carter early in 1951, and together they went to Europe where they stayed for nine months. First they toured in Italy, Switzerland and France where Cecil gained greater insight into the work of Picasso and the Cubists who had been held up to the Wits students as their most important models. Then they went to London where they both found work to pay their way. In his free time (released from the dirty dishes he washed at Lyons tearoom) Cecil frequently visited the British Museum where he was impressed by the collections of ancient art, such as Egyptian, Assyrian and pre-classical Greek. In time these impressions, and the subliminal messages from bygone civilisations conveyed through their art, would be assimilated into his own work. But his greatest discovery (in terms of his early development as an artist) was the large collection of African woodcarvings and Benin bronzes.

Skotnes also studied the contemporary art scene. He felt a strong affinity for the work of Henry Moore, especially the large pieces which he saw for the first time at the great Moore Exhibition in Battersea Park. He became a member of the British Contemporary Arts Society, and as such attended the opening by Kenneth Clark of a Graham Sutherland exhibition. The lingering influence of this artist on Skotnes is to be seen later in some of the anthropomorphic landscape woodcuts of the mid-fifties.

Skotnes believes that, had he stayed in England, he could have become a typical British artist. But he felt alien in England; he could not be creative there, and so, after a seven-month sojourn in London, he chose to return to South Africa and develop along uncharted lines. Back in Johannesburg, he took up an appointment with the Johannesburg City Council Non-European Recreation and Community Services, which led to his becoming the cultural recreation officer in the townships. In this capacity he developed the Polly Street Art Centre which, in retrospect, is acknowledged as greatly important in South Africa’s history of art. He also resumed painting.

Early landscape

My entire art grew out of the landscape. I tried to create a unique South African formal language by analysing the landscape – inspired by the forms which the indigenous art had already identified, and also against the background of Pierneef.3

Although Skotnes painted many still lifes at the beginning of his career,4 he emphasised the importance of landscape as a formative influence in the development of his iconography. Like several of his contemporaries (notably Erik Laubscher, Gordon Vorster and Gunther van der Reis), he strove to subject the scenery to a more cerebral formal construction. But above all he endeavoured to penetrate beyond the visual impressions of the South African landscape that had been recorded so well by earlier artists such as Oerder, Wenning and Naudé. Hence Skotnes’ interest in Pierneef who not only formalised the landscape, but, as Skotnes believed, was the first to lay the foundations for a uniquely South African pictorial idiom. The structured composition and the stark tone contrasts in the older artist’s work also appealed to the austere Skotnes temperament. His work still reflected the formalist training he had received at art school incorporating – particularly in the still lifes – unmistakable references to Cézanne. But even at this early stage a sense of universality with metaphysical overtones emanated from his work. He himself did not, however, burden his ideas about his art with deep philosophy. ‘My approach is simple,’ he said in 1962. ‘I attempt to interpret as realistically as possible the way I see my environment – that is my physical environment – and the spiritual influence it has on me.’5

His landscapes of the early fifties, almost invariably of rocky desert or rough mountainous terrain, entitled, for instance, Karoo and Basutoland, are harmonies of greys, contrasted with sultry blue, and occasionally enlivened by a flush of red. Formal structure, inspired by the contours, rocks and stones of the scene, is the essence of these compositions; colour is almost incidental. The artist’s main concern was to evoke a state of mind rather than the specifics of a region. The location is recorded primarily as a point of reference for the viewer.

At the time Skotnes set out on his career as a professional artist, Egan Guenther – a goldsmith and former gallery director in Germany – immigrated to South Africa. He had impeccable artistic taste, was well informed on contemporary art in Europe and also highly knowledgeable about African art. He readily recognised talent in others and encouraged and nurtured this not only by acting as dealer, but by means of animated and dictatorial discussions about art in general that challenged and stimulated his new South African friends and protegés.

Skotnes was introduced to Guenther towards the end of 1954; the meeting proved to be a turning point in the the artist’s career. In those years he was a painter and draughtsman and had not considered making hand-printed works. In fact, at the time woodcutting and the other graphic media were virtually unknown to him.

At Guenther’s I saw woodcuts at close range for the first time, and he gave me my first set of tools and showed me how to handle them. I also became acquainted with German Expressionism and the great similarities between it and tribal art, though I had developed a stylistic basis long before I became aware of the importance of the tribal art field.6

Guenther showed Skotnes woodcuts by several modern German artists, but he sensed that those by Rudolf Scharpf, a relatively unknown artist who had been one of Guenther’s protegés in Germany, would be of particular importance to the South African. Skotnes responded with alacrity, not only to the style and content of the prints, but to the medium of woodcut. While learning to use the unfamiliar technique, he discovered that, as he put it, he cut his shapes with greater surety than he drew them.7 In his enthusiasm he abandoned painting, only turning to it again seven years later.

The very earliest woodcuts – abstractions derived from rocks, thorns and grass – bear a close resemblance to those by Rudolf Scharpf, but soon Skotnes strove to create an essentially African idiom. ‘As chronicler of the South African situation I could not think in European terms,’ he said. ‘My approach had to originate here, otherwise my art would be a lie of little importance.’8 Consequently his designs became more harsh in appearance to evoke the African atmosphere of arid savannah and thorny bush.

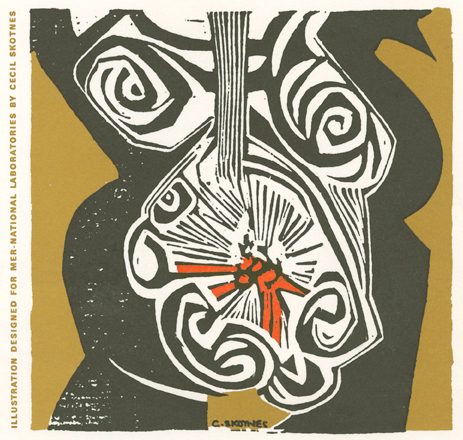

Guenther drew Skotnes’ attention to the beauty of the blocks from which prints were pulled, and suggested to him that the block could be refined and presented as a work of art in itself. In 1956 Guenther gave him some pieces of parquet flooring and suggested that he should cut designs on them. These modest carvings, intricate black compositions against white backgrounds, were to be the first of the Skotnes ‘incised paintings’,9 although not then identified as such.

From this time on Skotnes cut blocks from which to pull black and white prints. When the edition was complete, he embellished the gouged-out backgrounds of the better blocks with marble dust and coloured oxides, rolled solid black over the raised surfaces, and mounted them as autonomous works. The effect was, as Charles Eglington observed,10 not unlike stained glass with rich black set against luminous colour. But there is no suggestion that such panels simulate stained glass because the character of the wood always remains dominant.

Even though Skotnes regularly reverted to oil and watercolour painting and drawing with charcoal, chalk or pencil, the woodblock as an incised painting was to remain his favourite medium (besides print-making) for several decades. He sometimes adapted panels to serve as doors or pelmets. The earliest of these (commissioned by the architect, Donald Turgel, in 1959 to serve as the front door to his house) retained the prickly, angular shapes that had been inspired by natural veld vegetation. Later the scraggly, thorn bush-like figures with their agitated, dancing movement gave way to more readily recognisable human forms that face the viewers full square.

Also in 1959 Turgell commissioned the artist to make his first mural. Skotnes, who at that time was convinced that he was a cutter and not a painter, devised an unusual, perhaps unprecedented, technique for the work which suited not only his temperament, but the unconventional area on which Turgell wanted the decoration. The brick surface in question is a divider between two rooms and does not reach the height of the ceiling. It is continued outside to separate two areas of a terrace open to the sky. Nearby was a bank of weeping willows which inspired Skotnes, the landscapist, to bring, so to say, the garden into the house by repeating the trees’ general shape and rhythm, but in a drastically simplified and invigorated idiom.

Skotnes used a technique of coloured cement laid into lime plaster. The wall is covered with a layer of plaster, and, while it is still damp, the design is cut into it. The colour (in this case black) is trowelled into the cut-out spaces. The excess colour is scraped away leaving a crisp line drawing somewhat reminiscent, Skotnes says, of Japanese woodcuts on mulberry paper.

The artist used the technique to make several more murals in the same year. The designs are less severe than in the Turgell mural, showing a greater confidence which allows light-hearted humour to infuse the images as vivacious hominoid figures displace the earlier vegetation.

More commissions for murals followed. In 1963 Skotnes fell into a lyrical mood, inspired no doubt by the garden in which he worked, when he embellished an exterior wall of a private residence in Observatory, Johannesburg. He incorporated the shapes of the succulent plants, the lines of the foliage and vines, the patterns of the flowers, and echoed the shadows cast by the branches of a spreading tree nearby.

In the same year he adapted the inlaid cement technique to suit an exterior setting exposed to full sunlight for a three-storey high mural on the entrance facade of the Technical High School in Pretoria Gardens. The environment is harsh, dusty and blustery. He therefore created a design that resembles a wind devil reeling over the wide expanse of veld. The deeply gouged lines are not filled in with black plaster as in the other murals. The drawing is therefore grey, not black, and, during the course of the day, the image and quality of the colour change as the shadows and highlights shift according to the position of the sun and, on some days, the random vagaries of cloud.11

In about 1961, inspired by weathered primeval rocks and sunbaked earth, Skotnes turned to drawing and oil painting once more and made a series entitled Rock Faces (shown at the Egan Guenther Gallery, Johannesburg, in 1962). In these works Skotnes used colour evocatively. The surfaces glow with reds, yellows and ochres which are set against dark browns tinged with earth greens. A mysterious world seems to open up before the viewer, who is led into deep caverns of subconsciousness. It is in such places that religions are born. Beyond The Face of the Desert, The Place of Caves and Volcanic Castle we find Metaphysical Landscape, The Temple and The Altar. From them arose The Legend (Gertrude Posel Gallery). At the time Skotnes said, ‘Many shapes incorporated from my other paintings have been simplified in The Legend and it is perhaps the climax of my work’. Like the others, The Legend is an impression of a rock face. As in the real rock faces of our krantses it seems to teem with apparitions and phantoms that recall cities with tall buildings. These may metamorphose into the beings who populate such places and they, in turn, become symbols of our spirit and intellect.

In retrospect Skotnes claims that in these Rock Faces Willi Baumeister’s influence had asserted itself. He had discovered Baumeister (a German painter, 1889-1955) when he visited Egan Guenther in Johannesburg for the first time in 1954. There he saw a landscape painting which, he recalled years later, ‘was the most marvellous thing I had seen in years’. Athough at that stage he could not explain the elusive attraction it held for him, he immediately felt a profound affinity for it. During the seven years that he did not paint, the German’s vision became embedded in the young South African’s mind and it surfaced in the landscapes of the 1960s. Only later, after he had read his life story,12 did Skotnes realise how great his indebtedness to Baumeister had been.

Quest for the soul

As Skotnes painted his landscapes, recreating, as he said, the scenery as he saw it, his empathy with humanity and his awareness of metaphysical powers began to modify his iconography. Memories of the carnage of the Italian battlefields did not fade. The war experience initiated a life-long quest for the universal and metaphysical common denominator of humankind’s existence. He saw a similar quest in all art, whether classical Greek or African, Byzantine, medieval, Renaissance or modern. As time went on this preoccupation led him to analyse the essence of humanity through extensive reading about historic martyrs, heroes, rulers, councillors and delegates, all of whom had devoted their lives to the upliftment of humankind. These personages became for him archetypes of the human race and its intellectual and spiritual potential. The public soon became aware of the spiritual quality in Skotnes’ work, although many may have been at a loss as to how to define it. In 1965, when he had a solo exhibition at the Grosvenor Gallery in London, one of the reviewers drew attention to this mysticism:

The figures in the Martyr series have about them a religious quality, not in an ecclesiastical sense, but portraying an underlying spirituality in Man, in all Mankind. They are concerned with the existence of Man, timeless figures, not black or white, yet they arise from the artist’s response to his environment.13

Skotnes declares that his ideas flow from his brain to his hand. Therefore he may ponder with a pencil, chalk or gouging tool without first verbalising his concepts. This process can be seen, for instance, in a collection of small wood engravings which he made in 1979.14 They represent random thoughts, but they divulge the artist’s main preoccupations that recur throughout his career. These are universal concerns over which human beings have cogitated through the ages.

From a 1979 series of 22 woodcuts. No. 12, Beast threatening woman; No. 7, Veronica’s veil; No. 5, Warrior for Christ.

Confrontation between good and evil is a major theme. This may be depicted symbolically with colour or form, or personified by antagonists. In No. 12 in the 1979 portfolio, for instance, a beast – an ancient metaphor for humankind’s baser instincts – threatens a woman.

In other examples the confrontation may be between a male and a female, or a warrior and his enemy. The outcome of such a meeting can be problematical: is it glorious or degrading? Skotnes mulls over this in No.5. It was not the first, nor would it be the last time that he wrestled with the concept. When explaining the iconography of his mural, The Redemption of Man, he wrote: ‘The Crucifixion was always to man an heroic action, hence man’s easy use of force in the name of Christ . . . ‘ .15 This thought is implied in engraving No. 5. A centrally placed figure, with blazing eyes, bears the image of the Crucifixion on its chest. This ‘crusader’ stands large between two executed men. The meaning is ambiguous: at first glance theimage may be interpreted as Christ crucified with the two thieves on either side. But when one realizes that the image of Christ is carried on the chest of what looks like a pugilist, the interpretation is adjusted to recognize a warrior for Christ. The hanged victims may be his, but they could also be those whom he tried in vain to save. Such ambiguity – even paradox – is common in Skotnes’ work. It compels the viewer, like the artist to ruminate over the complexity of the human dilemma, particularly on a personal spiritual level.

Arcane icons and heads appear in the 1979 wood engravings too. These obsessively recurrent themes in the Skotnes oeuvre are the essence of the archetypes and heroes that populate the artist’s visual world. Some of these are given identities, such as Christ who is seen in No. 7 as the imprinted image on Veronica’s veil. Anguish and pain, the result of ruthless cruelty of one being to another, are paramount in these images. But an ecstacy of subliminal triumph is shown too; a transition from the conscious human experience to an unknown eternal exaltation.

Not all encounters, however, are confrontational. The human being can be in partnership with others and serve the community. Such beings can be recognized as mortal, with human foibles and humour, or, not infrequently, they appear to be incarnations in a metaphysical setting.

Spirit of the ancestors

I discovered a visual idiom in the indigenous art of Africa , the masks and woodcarving of the tribesmen, which was for me a direct expression of the African environment.16

Skotnes’ early knowledge and appreciation of the art of Africa was enhanced by the discussions he had with Maria Stein-Lessing, Egon Guenther and Vittorio Meneghelli, an Italian businessman with an all-consuming interest in art. Skotnes read widely on the subject, and as soon as he could afford to do so, began to collect African artefacts that originated in various parts of the continent. As his knowledge deepened, the collective forms of African art became an important influence on his style. He always acknowledged this source and recognised its diversity, but the various styles of greater Africa were melded together in his mind and imbued, too, with memories of his European heritage. Therefore he also cites as seminal to his art the influence of Cubism and in particular Picasso’s Cubist paintings. An example is the Demoiselles d’Avignon with its cruelly distorted bodies, and heads that are clearly derived from African sculpture. He also drew inspiration from much earlier, more universal sources. A primeval aspect attracted him to the art of the ancient Egyptian, Babylonian, Assyrian and Greek cultures. He is aware, too, of the influence that his environment and its people have on him. When Walter Battiss asked him in the early sixties what had formed his art, he replied:

The colours of Africa, but, as a European, I see the sensitive, bleached colours and the pale ochres rather than the strident, saturated primaries. I do large work because of the massiveness of the landscape. My creation runs parallel with that of contemporary, disturbed African art because the African and I are nicely caught in the same mesh of circumstances. I do not take from the African directly, nor does he take from me. What actually happens is that the black artist and myself, a white artist in Africa, are driven by the same artistic compulsions in parallel channels.17

Skotnes’ iconography changed gradually. Based in the late fifties upon the formalist aesthetic of his Wits training, it was subseqently nourished and vitalised by a more comprehensive and eclectic understanding of art and by a greater awareness of the world around him. He soon saw universality in African art, too:

Traditional African art did not take on its form fortuitously. It is based on structural characteristics that can be seen in the physical African environment in which we live. In time I began to isolate these smaller details and allowed them to take on separate shapes. A writer recently [that is c.1976] gave one of my early landscapes the title Figure Forms. And actually he was right – the elements into which I broke up the landscape gradually melded into my later mask heads and figure constructions. Eventually I could use those figures symbolically to express the South African situation within its own context. If in their symbolism and form they have given an authentic shape to the African environment because they grew out of it, then I am satisfied with the contribution I made.18

As has been noted above the Skotnes figures evolved, almost fortuitously, from the landscape. One of these (the first panel Skotnes was to show on the Sao Paulo Biennale)19 is on a tall, narrow format. The image is constructed of an exuberance of instinctively drawn planes crisscrossing as a non-figurative pattern over the entire surface. But at the top one discerns an impertinent profile with an unruly crop of hair. At the bottom the shapes taper into ‘legs’ supported by two clumpy ‘feet’. It was from such uncontrived (and playful) beginnings that the Skotnes figure style was to develop. In time the images became more overwrought, burdened with anger, fear and despair.

Skotnes always emphasises that when working he is preoccupied mainly with technical and aesthetic concerns, but he admits that form can never be entirely divorced from content and therefore his interest in the human being as a sensitive individual is always evident in his art. Almost inadvertently he has expressed his vision of the social and political changes in South Africa through his figures. They also reveal his search for a more righteous co-existence. These were symbolised for him in primordial cultures, but at the same time he recognised the irony of the human psyche in the ancient heroes. In 1972 Skotnes said that he saw the human environment as more violent than it had been in the past and that if the artist is not sensitive to the changes of his time, he is an outsider and his message is of no great relevance.20

During the sixties he attempted to alleviate his apocalyptic vision with humour and mocked the figures he designated Kings, Delegates and Councillors by satirising their appearance, giving them startled expressions or histrionic poses. But none the less, as one critic wrote, when ‘seen en masse [the figures] have an hallucinatory atmosphere as if one had been translated into a different climate, a different land’.21 It is historically interesting to note Battiss’ synopsis of Skotnes’ work in the mid-sixties:

The Africa of Skotnes – and of all of us – is now in the jaws of fate and is an Africa that is being shaken the way a lion shakes its prey. It is deeply significant that Skotnes reveals in dead earnest his angst of Africa.22

Via the woodcut Skotnes adapted his imagery, and to an extent his style, to correspond with what the public interpreted as an ‘African’ idiom. His subjects became anthropomorphic, derived from the African environment with its harsh forms, strong colour and contrasts in tone. In this he was not alone since Edoardo Villa, too, was exploring similar paths, and not infrequently a two-dimensional image by Skotnes can be seen as the sibling of a three-dimensional construction by Villa.

Egon Guenther, who had opened a commercial art gallery in Johannesburg in 1957, was particularly set on exhibiting work with a local flavour. He also wanted to show such work in Europe. Vittorio Meneghelli indicated his willingness to sponsor the venture. In 1963 Guenther therefore selected five of the regular exhibitors at the Egon Guenther Gallery – Edoardo Villa, Cecily Sash, Cecil Skotnes, Guiseppe Cattaneo and Sydney Kumalo – to unite in such an undertaking because in their work he saw a vibrant influence of Africa as expressed by individuals who were committedly South African, but from disparate backgrounds. Villa and Cattaneo were Italian immigrants; South African born Sash was Jewish; Skotnes, although also South African born, came from Norwegian-Canadian stock; Kumalo was Zulu. The group was called ‘Amadlozi’, a Zulu word meaning ‘the spirit of the ancestors’, an ideal name for what Guenther had in mind.

Shortly after its formation the group’s first exhibition took place at the Egon Guenther Gallery in Johannesburg. Thereafter it travelled to Italy where it was shown in Rome, Florence, Milan and Venice. Although the group as such soon disbanded it served not only to promote South African art overseas, but also to underscore the significance of the African prototype and atmosphere. It stood as a pointer in the development of South African art, leading towards a new understanding and appreciation of artistic style and language. In that way it helped break the barriers of what had been the hidebound Eurocentric attitude of the majority of South African art patrons.

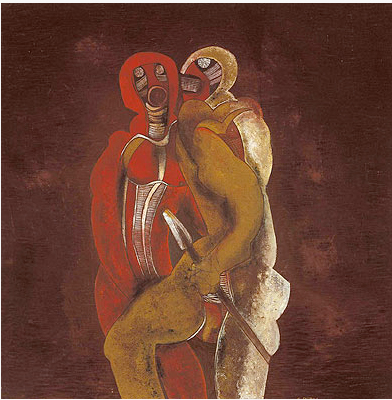

At the time of Amadlozi’s first exhibition, Skotnes’ iconography and style were distinctive. Severely abstracted, boldly cut figures fill the formats. They call to mind fantasies of the reincarnations of ancestral figures, charged with aggression. But the vicious aspect of the Skotnes imagery is bluff, for it is soon evident that the strange hominoid creatures with their feinting and posturing are vehicles of the ironic Skotnes paradox in which the eternal mystery of the human psyche is countered by humour and ridicule. Such ambiguity always intrigued Skotnes. He endeavoured to probe and understand the fundamental character of humankind, but simultaneously he encountered flippancy and fickleness, grandiose ambitions and feeble achievements, venerable idealism and tragic failure.

Other avant garde South African artists of the sixties were, like Skotnes, also striving to create a local identity in their work; they wanted to be unequivocally recognised as South African – not European or American – when their art was shown abroad. They proclaimed what they recognised as their heritage, which, they all agreed, was EuroAfrican. This idea was re-iterated in the 1969 edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica which brought it to international attention:

South African artists, surrounded by the light and forms of Africa, instinctively responded to the same stimuli. Almost for the first time South African art – whether figurative, graphic or abstract – became unashamedly of Africa.23

A reproduction of Skotnes’ incised painting, King and Two Councillors, made in c.1964 and owned by the Peter Stuyvesant Collection in Amsterdam, was used to illustrate the point. This was the first time a work by a South African artist had been published in the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Albert Werth, who examined the influence of primitivism on South African art24) suggests that Skotnes, of all his contemporaries who were striving to be ‘African’ in their work, perhaps demonstrates the clearest influence of classical African art. The majority of critics at the time insisted on seeing Skotnes’ work as essentially ‘African’, but Neville Dubow queried this:

It would be wrong to overstress the ‘African’ content of all his work. Obviously it is there in his more literal work … But in his more intellectually astringent studies … there are design principles evident which are almost universally applicable to any linear system of ‘primitive’ expression. In other words there is as much of the aboriginal Australian bark painting about them as any African example. They are in fact the product of a very skilful designer who is heir to a wide spectrum of precedent.25

On another occasion Dubow remarked:

Where Skotnes is absolutely in a class of his own is in his ability to synthesise this traditional [African] approach with outstandingly inventive and fertile imaginative resources. And these are essentially private and personal to him.26

In an analysis of a relatively early work, The Delegates 1963, (Pretoria Art Museum), Riena van Graan also saw more than a generalised African influence in Skotnes’ style:

As regards Skotnes’ spiritual attitude, I personally see more in his iconology than the spirit of Africa. Man as created by this artist is more than a fetish or a tokoloshe … and does not ‘belong’ to any particular race or culture: the symbol of man created by Skotnes is a universal and timeless man equally representative of man in our technological age; reminiscent, in some instances, of the hierarchic figures of ancient western cultures; in fact, it could even be seen as a symbol for the first man on earth.27

In 1965 Skotnes himself said:

The art of the sub-continent cannot be split into white and black. I believe, artistically as well as morally, that what I am doing today, and what the African artist of the sub-continent is doing today, is part and parcel of a single southern African movement.28

Archetypes and heroes

As Skotnes perused a variety of books, wandered through temples, churches and museums, and acquired artefacts and works of art, his mind stored and assimilated impressions. These re-emerged often very much later – adapted and personalised in his art. There is, however, a constant: the expression of the psyche of humankind. Skotnes’ children remember that the bed-time stories he told were the myths of ancient Greece. Their arcane psychological truths will have escaped the children, but no doubt it is these that fascinated the artist. Among his favourite haunts are archaeological sites where he imagines that he can sense the presence of the spirits of the gods and people of long ago:

They have a quietness about them [he said], a stillness, they’re there. They are spiritual statements. They are not peopled by living things, they are peopled by great thoughts, great poetry. They are places where mankind lived, and they show the work of his hand and of his mind. So they are more acceptable to me, more metaphysical than the places where people live today.

His heroes are the prophets, leaders and warriors of archaic civilisations. In them he tries to find – unconsciously, no doubt – what may be described as a Jungian archetypal model by which to understand his fellow human beings. This search exposes his temperamental affinity with Willi Baumeister. He was to discover the relationship – and consequently understand the immediate attraction he had felt for the German artist – when he read Baumeister’s life history.

Baumeister, a proto-Expressionist, was interested in African and Aztec art. He was passionately absorbed in the study of prehistoric art and ancient cultures which led to African Histories, a ‘series of paintings of weird, organic forms, usually in an earth colour on a white ground – all of them strongly impregnated with the prehistoric and the archaic’.29 (This nearly describes the Rock Faces by Skotnes.) Another series was entitled Metaphysical Landscapes (and Skotnes was to paint such landscapes too, populated by strange beings). Baumeister illustrated the Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh, a tragic hero who is sometimes regarded as the Babylonian Faust. (Skotnes dedicated an exhibition to Gilgamesh as well. He again referred to the epic on a panel made to hang in the dining room of the Cape Dutch homestead, Laborie, in Paarl, and an incised painting entitled Gilgamesh was shown at the South African Association of Arts Gallery on the 1994 Skotnes exhibition in Cape Town.) Baumeister was inspired by biblical – especially Old Testament – and mythical figures, and these are favourite subjects for Skotnes, too. Superficially the Baumeister works appear to be solemn and austere, but the archaic figures are often capriciously light-hearted. Temperamentally and artistically Skotnes is a true descendant of Baumeister.

Through mythological, biblical and historical heroes Skotnes endeavoured to understand the archetypes of humanity. The word ‘archetype’ is often loosely used without knowing its exact meaning. The Oxford Dictionary defines it as ‘original model, prototype, typical specimen’. That is the meaning Skotnes gives to the word. The dictionary also gives its psychological connotation (coined by Carl Jung) as ‘primordial mental image inherited by all; recurrent symbol or motif’. ‘Archetypal images,’ Jung said, ‘are among the highest values of the human psyche; they have peopled the heavens of all races from time immemorial.’30

To use the Jungian terminology in relation to Skotnes’ iconography may be questioned, or regarded as suspect and pretentious (particularly since the artist has not read any of Jung’s publications), but I find it illuminating. Much of what Jung said about archetypes to a large extent describes the Skotnes figures as I see and experience them.

Jung isolated an old, wise man, who can be king, hero, medicine man or saviour – for he is endowed with a compelling power – as an archetype which has existed since time immemorial. He has two aspects: light opposed to dark, and good and noble opposed to sinister and evil. Something strangely meaningful clings to the archetype, a secret knowledge or hidden wisdom. Archetypes are mediators between the conscious and unconscious mind, and when they become personified (in art, for instance) they present an opportunity to understand something of what has hitherto been unconscious. Such images have the power to arrest the onlookers’ attention, but it is difficult, often impossible, to explain the fascination or to interpret the significance of the image.

Skotnes’ art drew attention from the outset of his career. This is easy to understand insofar as his landscapes and still lifes are concerned, but that his redoubtable figures should have acquired such a great following can only be ascribed to the subconscious fascination felt for the archetype. Admittedly many, not unintelligent, people dislike his iconography because they are repelled by the harsh, apparently crudely drawn figures with their truncated limbs, visceral torsoes, mask-like heads and belligerent attitudes. Quite often these affronted viewers feel compelled to air their objections:

I ask most sincerely, because I really want to know – What goes on here? Why does Cecil Skotnes make these ghastly-looking things, and why do people buy them? What is beautiful about these figures, vaguely human and looking like the cross-sections of skulls of unhatched birds? And these hard, dry gourds dangling where breasts ought to be? Is this what life looks like to him? Why are these works (obviously a lot of time has gone into them) regarded as art? Isn’t art supposed to be an expression of beauty? What must I look for [in the Skotnes works]? I sincerely want to know, because I might be missing something big. Or is my taste and feeling such that I cannot see whatever it is of beauty that other people see in these weirdies? Have I a blind spot, or am I simple, ignorant (innocent?) like the small boy in Hans Andersen’s tale about the Emperor’s new clothes … ?31

This is not a frivolous letter to a newspaper editor, but one from a cultured person who is disturbed not only by Skotnes’ art, but by the enthusiastic reaction of others to it. As such it could be dismissed, but for the fact that the writer obviously looked carefully at Skotnes’ work and was involuntarily intrigued by it. Something in it drew her to it; something demanded her attention, and something intimated to her (although this she did not recognise) that the work contains a spiritual message that could be relevant to her.

Despite the bewilderment many people feel, multitudes of viewers are drawn to the images. Initially they may be repelled by the distorted imagery, but are attracted none the less by its power. Then gradually they come to understand the force which in primeval times compelled people to worship idols. At last they detect the ironic humour, and as a result they may recognise their psychological selves and their friends in the Skotnes images.32

The earliest mural in which Skotnes envisioned a timeless, philosophical-religious gathering of people was The Redemption of Man, made in 1965 for the Roman Catholic Cathedral in Kroonstad. Although the theme was contained within the narrative of the Old and New Testaments, its meaning went beyond the depiction of specific groups of people and came to symbolise humankind.

Within the following five years Skotnes made three more major murals. Two of them are composed of vividly coloured incised paintings on large panels to cover the walls. The first, its eight panels each one and a half metres high and extending for almost fourteen metres, was completed in 1966 for Barclays Bank in Commissioner Street, Johannesburg. In 1969 a smaller mural (260 cm x 610 cm), consisting of five panels, was made for the Standard Bank Head Office in Johannesburg. Both murals are entitled The People. The artist says, however, that they could just as well be called The Village because, while The Redemption of Man symbolises humankind, the secular murals are metaphors for people who are confined to closed communities that are circumscribed by separate villages – ‘the places where you live, and do things, and die, and resuscitate, and so on,’ he said. In such places life is determined by tradition, mores and rules that are laid down by the elders. Such autocratic leaders Skotnes regards as manipulators of the fate of their people and thus they may stand for tyranny in general. They attempt to subjugate their people, despite protest and revolt that are symptomatic of humanity’s eternal yearning for freedom. Freedom means severing those ties that bind individuals to the masses. Ideally individuals should break free and make personal choices. But the group is so intertwined and wrapped within itself that, ironically, any sense of freedom that there might have been is false. Human beings remain like puppets who have no control over their destinies. And so ‘the people’ remain in the village ‘from beginning to end, and beginning again,’– a procession for eternity.

Also in 1969 Skotnes began work on what is one of the largest murals in South Africa – the approximately 2,5 metres high and 35 metres long western outer wall of the Hyde Park Shopping Centre in Sandton. Once more masses of people are depicted, but here there are many more than in the villages and therefore the mural is entitled The Citizens. It is executed in the sgraffito technique – scraping away the plaster surface to reveal coloured layers beneath. The lowest layer is a very dark charcoal grey. A layer of white, alternated with rust and ochre oxides at predetermined places, is superimposed upon this. While the topmost layer was still damp the figures were cut and scratched down to the level of the desired colour with anything from broken saw blades to kitchen utensils.33

The head, which features so prominently in these murals, is as important as the figure in Skotnes’ iconography. Occasionally it even displaces the figure to represent a heroic character or concept. An unlikely source proved to be its origin. The artist recalled that, in the mid-fifties, he saw a wicker-work chair

which had a malacca cane structure with batons to support your body at the back. I drew the chair, which was curved, and I cut out the negative spaces leaving the black lines for the structure. When I turned it [the drawing] upside down it became a face. Obviously that didn’t happen the first time I looked, but it certainly developed in the first three or four months34

Subsequently he also saw the rudiments of heads and faces in natural forms in the landscape. But, as in the case of his depiction of the human figure, the heads are also heavily indebted to Picasso’s Cubist work. In addition Skotnes identifies the helmets with narrow slits for the eyes and rectangular nose guards – that were worn by the ancient Greek hoplites – as another source for his heads.

Skotnes is adamant that the images are heads, not masks, even though they appear to be closely related to tribal masks visually and are quite often designated as such. ‘As far as I am concerned these are all heads. I entitled them masks only when I saw a formal relationship between the work and African masks.’35 His aim with the earliest heads was purely formal. He endeavoured to create interesting visual tensions which could be as powerful and evocative as those found in African art:

From 1956 I was working in a two-dimensional manner, black and white woodcuts. It allied itself with the technique of cutting in the making of the woodcut and I established a relationship between African masks and some of my works.36

In 1994 Skotnes told me that the first time he intentionally drew masks as masks – that is as false, superimposed personae – was in the eighties. In his cruelly satirical drawings, which have profound religious philosophy embedded in them, he simultaneously comments bitterly on the social and political situation in South Africa. In these drawings he depicts

… strings to show the guy’s got a mask on – that means he’s changing his personality, he’s another character, like in the Greek theatre. So the mask then builds in another force, becomes another personality. And that goes for tribal masks.37

The earliest heads are single images, often disproportionately large with the merest indication of shoulders and torso. They are almost invariably depicted full-face. An austere outline frames a face criss- crossed with striations. Circles or radiated discs indicate startled or threatening eyes. Below these a smaller circle or, less commonly, a horizontal line, represents a mouth, sometimes puckered, sometimes formed to speak, sometimes clamped shut. The vigour and distortion of the designs are threatening at first and viewers recoil as they would when approached by a feinting tribal dancer in full regalia. But when one notices the ludicrous eyes and the even more ridiculous mouth, one recognises the fake bravura that attempts to disguise the vulnerability of the persona – and one laughs, bitter-sweetly, however, because the psychological truth conveyed by these images relates to all humankind.

Gradually the Skotnes heads gain psychological potency that reinforces their aesthetic formality, and they come to reflect all the inherent qualities of the human race. They become visualisations of the archetypes. This is patently evident in The Redemption of Man where Skotnes created groups of heads to represent the Patriarchs of the Old Testament and the citizens of the New Jerusalem, while a solitary head symbolises the risen Christ. In the Barclay’s Bank and Standard Bank murals the centrally placed, monstrously large heads symbolise forces that inspire or bedevil human behaviour.

Skotnes mulled over this idea in numerous panels depicting heads, which he made concurrently with or shortly after the secular murals. Despite the given titles of some of them, and the reviewers’ regular reference to them as ‘masks’, Skotnes claims that none of these heads is derived from African masks; they are his visualisations of psychological states which he feels can be expressed in no other way.

When Skotnes was making the murals for the banks in Johannesburg some of the ‘village dwellers’ managed to ‘break free’. Five joined forces in a composite work entitled The Altar (Pretoria Art Museum). Are they priests, acolytes or worshippers? Or representatives of each of these? Other ‘escapees’ are solitary, like Martyr (Pretoria Art Museum). Collectively Skotnes called such tall, slender works Totem or Totem Figure, thereby once again indicating his fascination with aboriginal (in this case North American Indian) life and art. These images were usually made on planks, worked on both sides so they can stand free and be viewed from both sides. Others were carved from solid wooden beams. Often – like the group of The Altar or Martyr and Totem Figure – single, attenuated figures fill the formats, but others resemble North American totem poles more closely in that a number of images are carved and vividly coloured in a tall, vertical array.

In 1971 Skotnes won a competition to make a mural for the foyer of the Ciba-Geigy office building in Isando, Kempton Park near Johannesburg. Diverse, and what may appear to be unconnected, thoughts crowded his mind when he contemplated the wall. The overriding idea was technical: he would use the big, heavy wooden beams he had recently managed to acquire. The possibilities excited him because he had never used such beams in a mural before. He wanted to set them against black Belgian marble, but when he learnt how expensive that would be, he elected to use precast stone instead. Without hesitation he decided to decorate the beams like totem poles:

And then immediately I thought about Romanesque churches. The round disc at the top is really a rose window – a religious symbol. The three heads were conceived in terms of the architectonic design of the wall in its environment. As was the case with the other murals I took cognisance of the area in which it was set. Placing a religious symbol on it was right, but it wasn’t because I wanted to imbue the chemical company with anything that would make them look as if they were going to church! I just thought it was a good space.38

These reminiscences provide insight into the working of the artist’s rich, eclectic mind. North American totem poles are effortlessly united with Romanesque portals. Without compunction he accepts all religious expression as compatible and all-embracing, arising from universal psychological and spiritual needs. Therefore, totem figures standing sentry in a landscape could just as well be column figures that guard the entrances to medieval churches.

The rose window (or oculus when – as in the Ciba-Geigy mural – it has no radiating design), is an expression of the mandala, a Sanskrit concept meaning magic circle. Skotnes emphasised the reference to Romanesque churches, and in its general appearance the Ciba-Geigy mural is indeed reminiscent of the central part of the western façade of Chartres Cathedral with its oculus below which is a triad of wide, arched windows and beneath them the Royal Portal with its serried columns.

Skotnes understood and appreciated both the Romanesque sense of architectural cohesion and its epic iconography. He would agree with the medievalist, Henri Focillon, who said that the Romanesque artists ‘bestowed super-human proportions on God-made-man and man-in-the-image-of-God; sometimes they even gave them an appearance divorced from humanity’.39 These were the characteristics Skotnes wanted to redefine in his mural by means of his own imagery.

The designs on the uprights are so abstracted as to be almost non-figurative. Distortions of human figures can, however, be discerned in them (thus recalling both twelfth-century column figures as well as American Indian totem poles), but, prompted by the tall plants the company has placed near them, the shapes can also be interpreted as proliferous vegetation. This, too, is a feature of many Romanesque columns where interlacing vines clamber upwards around the cores. The artist affirmed that he wanted the designs to lead the eye to the culmination point in the oculus.

The three heads recall the triad of windows on the Chartres west front. Unprompted, Skotnes said that these heads were ‘conceived architecturally’, so he may well have been subliminally inspired by the Chartres windows. In the façade the centre window is taller and wider than the lateral two and therefore it appears to be dominant. In the Ciba-Geigy mural Skotnes achieved the same effect by showing the middle head full-face and colouring it white and red – two of the most aggressive colours – while the lateral heads are in profile, each facing the one in the centre. Their colour is mainly a muted, recessive ochre. No wonder, then, that when one is aware of the artist’s reference to religious prototypes, these heads may be interpreted as priests if not divinities.

The disc above is embellished with an intricate design in brilliant red and white against a deep black. The colours in themselves are emotive and over the ages have been given potent symbolic connotations. The shapes are non figurative, but can be read as arcane signs intelligible only to initiates.

To complement the mural, which covers the two storeys of the narrow wall of the foyer, Skotnes made five more works – three small piers and two panels, – to hang in a corridor behind the foyer. Although they are readily visible (in fact, the visitor may see them before noticing the mural which is directly alongside the entrance), these works are remote, but they nonetheless cohere most satisfactorily with the mural and add substantially to the aesthetic quality of this public area of the building.

The Shaka epic

The three stabs of betrayal (by Mhlangane, Dingane and Mbopa) on 22 September 1828 drove into the Zulu earth the subcontinent’s greatest despot – Shaka. But his myth – of the illegitimate weakling of a lowly clan turned warrior, hero, defender, empire builder and god – keeps living on. History and legend here fuse to retell the drama of the people of thunder.40

Besides its aesthetically principled formalism, Skotnes’ art also always conveys a psychological, metaphysical, or spiritual message. Sometimes it tells a story. But Skotnes does not merely illustrate the text that inspired him; he recreates it. His pictures are therefore not subservient to the words (as illustrations often are), but complementary works of art that in some cases overtake and overshadow the text. This is true, for instance, of the illustrations he made for Tales, a collection of poems by Sinclair Beiles, in 1972. Instead of visualising the poet’s images, Skotnes recreates the atmosphere of the verse, and the woodcuts can stand independently of the poetry. This independence is even more evident in any illustrations that Skotnes initiated, inspired by what he read or experienced. Such was the case when, in the early seventies, he read E A Ritter’s book Shaka Zulu,41 the history of a man that was bound to fire the artist’s enthusiasm.

The Shaka epic was visualised after I became acquainted with the main elements of his story. It started as an interest in the man, and became an obsession to give him his rightful place as the most important historical figure of the first half of the nineteenth century. There had been an attempt by both black and white – Dingaan and the British – to smother his importance, to turn him into a vague monster whose impact on the times and the future was equally as vague. I intended to rectify that and present him as the great figure he was. He appealed to me for several reasons: hero in the classical mould, warrior, statesman, ‘creator of the Zulu empire’, tactician and commander. Owing to his action the whole of the tribal life of southern Africa, even as far as the great lakes of central Africa, was redistributed , thus laying the foundations for firstly the white move into the interior and subsequently the establishment of the various presentday black states, but I also wished to maintain the legendary aspects of his character.42

At the time Skotnes was reading Ritter’s book, Vittorio Meneghelli showed him a magnificent old door of heavy, solid wood, divided into 47 small panels. Meneghelli, an art collector who counted many artists among his friends, told Skotnes that he wanted to ask several of them to decorate a panel each, including Skotnes. Skotnes’ response was to say emphatically that nobody else but he was to touch that door. He carved Shaka’s story on it. The complete work is, he said, ‘a direct interpretation of Shaka’s life, each panel or incident made in historical sequence, and overall it was slanted towards the hero figure.’43

Skotnes regards this door as a ‘block book’, that is, a story told in pictures without words. His models were medieval and Japanese block books and, above all the twentieth-century example made by Frans Masereel, the Belgian Expressionist woodcutter who cut in block prints his indictment of the social upheaval of the twenties. After completing the door, Skotnes remained engrossed in the Shaka theme.

I was totally absorbed by the man and loved him as I probed his story. He seemed to laugh at civilization as we know it. He indicated that the new Africa would take what it wanted from our world and use it for its own purposes. He after all set in motion everything that besets civilization here and now. The idea was SHAKA, and Shaka became the giant that set in motion the force – the winds of change – that will destroy the world as we know it, the world we already doubt. It was like the Norsemen in Europe.44

Therefore he suggested to a friend, poet Stephen Gray, that together they should make a block book in the form of a portfolio with images and words. ‘We did an enormous amount of research, and actually travelled the route from Shaka’s birthplace to his Great Kraal,’ Skotnes told Denis Godfrey. He worked on the project for almost fifteen months, making drawings, watercolours and the 150 blocks needed for printing. Concurrently he also made large panels depicting characters from the saga. One of these, U Shaka (or Shaka the God) (Pretoria Art Museum), was completed in December 1972. The artist still considers this panel to be the best in the Shaka series.

On 20 October 1973 the portfolio, The Assassination of Shaka, was exhibited at the Goodman Gallery, Sandton, and, despite some negative criticism, caused a sensation.45 The 225 available copies were sold on opening night. Disappointed collectors and bibliophiles had to wait until the following year when McGraw-Hill published the portfolio as a standard book.46 At the time of the exhibition Skotnes said:

I don’t think anything as big as this has been done here before, and it is debatable whether an epic story of these proportions has ever been done in woodcuts and poetry in this country. Because of the medieval character of the woodblock technique and the use of free verse, we get down to fundamentals, which is what Shaka was – a fundamental figure in southern Africa’s history.

His is, in fact, an epic of all Africa. Shaka matches the great mythological figures of the ancient world in every aspect of his life, and thus, in less than 150 years, we have a figure of this stature on the horizon of our history.47

In April 1974 Skotnes donated an incised painting of the Zulu hero, as well as some of the blocks used to make the prints in the portfolio,48 to the recently established Touch Gallery in the annexe to the South African National Gallery in Cape Town. In her letter of acknowledgment the curator of the gallery wrote:

It is exciting to see sighted visitors, fresh from the Assassination series in the main gallery, entranced by the opportunity of being able to appreciate your approach through a tactile sense. The blind have responded eagerly, too, and suddenly realise why their practical sessions have revolved around a two-dimensional approach. People who might otherwise not have heard of the Touch Gallery are now interested in the set-up as a whole.49

The Cape Times placed a photograph of a blind visitor from Guguletu discovering the image on the large panel, and recorded her response: ‘It has a head – arms – legs, they’re pointed, like assegais! He has no feet.’ The expression on her face changed from a frown to a gleam of delight as she began to perceive the form on the wood.50

On 10 May 1974 the artist and poet went to Nongoma to give a portfolio to the Zulu people. It was received by King Goodwill Zwelithini at a splendid ceremony. In closing Chief Mangosothu Buthelezi called

… his venerable aunt, oldest female praise-singer of the house of Senzangakona, father of the Shakan dynasty. And she, eyes closed, body clenched, had us stand; and she launched into a rhetorical display that tape-recorders and movies and books don’t seem to have caught – a living, virtuoso, magnificently-controlled, tense, praise-chant, and a full-spate, musical battering of words as codified history, as epic drama, as celebration, with the praises of Senzangakona … ‘Bayete! Bayete!‘51

The heroic Zulu continued to haunt Skotnes. In May 1974 the Goodman Gallery presented an exhibition comprising thirteen incised paintings, some of them very large, and fourteen drawings and watercolours that reiterated the Shaka theme.

One of the large works, a triptych, The Death of Shaka, was commissioned by the South African National Gallery. The carving of the blocks was preceded by sketches in watercolour (South African National Gallery) that contain the fury and violence of innate savagery. The completed panels are more controlled, the emotions harnessed, so to speak, within the confines of surface design.

Artistically Skotnes had exhausted the theme, but the art world still clamoured to see it. As a result an exhibition of Zulu artefacts was shown in Vienna with The Assassination of Shaka as its centrepiece. Cecil Skotnes was invited to attend the opening and to address the visitors. Crowds came to see and to learn. News of the exhibition spread resulting in museums in Germany, France, Monaco and Belgium asking to show it, too. Europe’s artistic eye (as opposed to its hostile political eye) was suddenly focused on the sub-continent and Skotnes acted as South Africa’s cultural ambassador.

Borne along by the success of The Assassination of Shaka Skotnes and Gray were inspired to make more block books, albeit on a less ambitious scale. The White Monday Disaster, telling the story of Wolraad Woltemade, and Baudelaire’s Voyage to the Cape followed in quick succession. Concurrently with Baudelaire’s Voyage Skotnes made ten coloured woodcuts to illustrate poems of his deceased friend, Charles Eglington.52

Since all the portfolios and the McGraw-Hill publication of The Assassination of Shaka had generated unprecedented profits, artist and poet undertook to plough back some of the proceeds into a publishing venture, the Quagga Press. It would concentrate on the reissuing of key works of South African fiction, beginning with the republication in 1975 of Mhudi, the first English novel by a black author, Sol T Plaatje, written in about 1917. Skotnes made the woodcut illustrations for it.53 The publishers obtained the rights to produce other titles, but after the appearance of Mhudi, the Quagga Press amalgamated with another firm, thereby conceding its imprint.

The Underground

beneath a hill of human bones

a swaddled group

laments and groans.

one dares to cry he’s crucified

what answer can he get from

relatives who died

and gardened him below

as if some seed to sow?

whate’er his breed

man is not seed

begins to sing the underground

and there’s a tremor in the earth

at this frightening sound.

how will they rise from out their grave

and standing on the hill of bones

how will they behave?o do not ask

one thing we know

they will not show.– Sinclair Beiles54

Visit to a Battle Site 3

After the tumult of the Shaka experience which took the art world by storm, Skotnes felt artistically drained, and he craved silence. He found it in his memories of the desolate battlefield of Isandhlwana in Natal. He was sensitive to its eerie stillness, and aware of the souls that haunted it. He said that the battle site paintings grew out of his whole spiritual vision.

Visit to a Battle Site 1

I attempted to create the silences. The silences I sense when I stand in front of the Piero [della Francesca] Christ Rising from the Tomb or the Duccio Maesta in Siena, and The Charioteer of Delphi. The battle site was lsandhlwana in Natal, but it could have been any monument to man’s folly. After all I have strode over battlefields when the smoke was still all-embracing and the roar of guns is still in my ears. There is a religion in silence – the stillness is a wilderness and that term wilderness is loaded with tradition – the great wastes on which a whole generation of slave Israelites died out, even their leader Moses, so that only those who knew nothing but victory would inherit the new world. The battle site pictures are really an attempt to put all the elements of my artistic output into single compositions. That, of course, failed, but the fragments were larger and therefore more lucid. After great noise the silence is almost unbearable – it is the mind and spirit summing up the causes of the cataclysm, and those who pause to understand usually never survive. They are the spirits of reason, and our times, while taking cognisance of reasons, never indulge in reason. The creative souls can and usually do quickly sense the times and are usually first to set down their reactions. Also at the moment of conception there is no fear. Those figures on the battle site are not the ghosts of dead men – they are the understanding of what is to occur or the wilderness created by storm.55 The silence of the battle site lets the spirits live again.56

Visit to a Battle Site 7

I made several pilgrimages to lsandhlwana, the great battle site where the Zulus destroyed a British army in 1879, before even thinking of attempting to depict the site. When I was preparing for The Assassination of Shaka portfolio Stephen Gray, Thelma and I were taken to the site by the Reverend Anthony Barker, a doctor missionary at a local hospital. It was a deadly quiet warm day which heightened the long-ago dreadful sound of battle and the protests of the 4 000 dead who must surely still roam that broken plain. The white stone cairns which straddle the place, showing where each English regiment died in defence of a dubious cause and the lack of any visual funeral artefacts to honour the Zulu dead. I’ve read almost everything about that conflict, mainly official documentation. However, I have an addiction to battle sites. They were burnt into my consciousness in a dozen or more places in northern Italy before I became a painter, and the awesome results of war are so easy to recall, especially in those hours before dawn breaks.57

The battle site pictures were exhibited at the Goodman Gallery in Sandton in 1975. They inspired the critics, and therefore some of the reviews are reproduced here with no further commentary since they recreate the general response – even today – to these intensely personal works.

Visit to a Battle Site 14

‘Paintings on a visit to a battle site’ reflect the remarkable spiritual effect that a visit to such a site as lsandhlwana induces – for although he doesn’t publish the scene of his experience , that is where he found his inspiration. Skotnes has conveyed the supreme loneliness of the place, the utter quiet and above all the presence of an invisible host – the men who died and are buried beneath the white-washed stones. I have visited this famous battlefield on several occasions and I have remarked on the complete absence of sound, even of the crickets which are so characteristic of the veld. All this is present in these superb paintings. They are abstractions with an element of realism and they would make a splendid mural for any memorial on the site, one which I think anybody would understand’.

HE Winder

Rand Daily Mail, 14 March 1975

Visit to a Battle Site 12

Cecil Skotnes is an artist with a special affinity for Africa and he has found fruitful means of expression through rediscovering aspects of its heroic past. The spirit of Africa pervades his work and history becomes art in his latest series of paintings … These large canvases are the artist’s response to the scene of the battle of lsandlhwana in 1879. Entitled Visit to a Battle Site, the paintings do not tell a story but consist of figures set in different metaphysical landscapes – timeless figures which speak of the blood, isolation and misery of war. There are faces which ask questions about glory, victory and honour. Skotnes visited the battle site during the course of the research for his portfolio The Assassination of Shaka. He was struck by the fact that although there were cairns of stones for the British dead, nothing marked the graves of the Zulu warriors. Three thousand Zulus died in this, their last successful onslaught before final defeat. Their heroism is not recorded for posterity. What is remembered is that the Zulu King gave permission for the people to weep in the villages despite their victory. This is what moved the artist. ‘The echo is so relevant to the times in which we live,’ he said.

Natalie Knight

The Star, 7 March 1975

Visit to a Battle Site 13

These sombre and dramatic paintings with their half life-size figures boldly assert their presence and power while recording his visit to the site of the Battle of lsandhlwana of 1879. Here Cecil’s deep interest in the Zulu nation … is extended and encapsulated into a statement of profound significance. Making an immediate impact on the senses, each painting asserts itself through the masterly handling of rough, earthy textures united with the subtlest of ochres, pinks and blacks – all alive with atmosphere. The visual idea of the figures encompassed and enclosed by the high horizon strongly suggests living forms becoming living spirits – lingering for eternity at this sight of blood and momentary triumph. A grave indeed for brave Britons and Zulus who died for a forgotten cause, but somehow still relevant as we, nearly one hundred years later, struggle to live together in peace, harmony, and goodwill.

Larry Scully

Sunday Express, 9 March 1975

Visit to a Battle Site 8

Skilderye oor ‘n besoek aan ‘n slagveld boei nie net onmiddellik nie, maar laat ‘n mens ook met ‘n gevoel van aangename verrassing. In hierdie lien skilderye bereik die kunstenaar, wat met sy houtsnee en gekleurde houtpanele bekend geword het, waarskynlik vir die eerste keer ‘n hoogtepunt in die skilderkuns. Die grootste lof wat ‘n mens die skilderye kan toeswaai, is dat hulle geen geskilderde houtsnee is nie, maar skilderye in hulle eie, skilderkunstige reg. En dat nie almal van hulle dit is nie, is bloot ‘n bewys van die ontsaglike stilistiese stryd wat die kunstenaar in die oliemedium moes voer, asook van die verdienstelikheid van sy uiteindelike oplossings. Die drie skildrye [No.4 , 1.36, No.5, 1.37 and No.7, 1.31] wat as skilderye – nie heeltemaal wil slaag nie hang ook in ‘n afsonderlike vertrek. Hulle is waarskynlik die vroegste geskilder, want hier vind die kunstenaar dit nog duidelik moeilik om die grafiese stilering van sy houtpanele aan te pas by die meer ruimtelike, atmosferiese medium van die skilderkuns. Die doek van die skildery is nog benader soos die tweedimensionele oppervlak van ‘n houtpaneel. Ruimtelike diepte ontbreek en die stormagtig e, gejaagde kleurgebruik verraai Skotnes se onsekere soektog om dimensie langs die weg te bereik. Die poging tot ekspressiewe diepte in die wolkerige kleur word egter gefnuik deur die houterige liniere strakheid van die figure wat almal in een statiese vlak langs mekaar ingeskets is. Skotnes maak self ‘n byna wanhopige verwysing na die dominering van die houtsneestyl in hierdie werke wanneer hier en daar hy ‘n figuur uit hout gekerf tussen die geskilderdes monteer. Dit verteenwoordig ‘n onsuksesvolle poging om deur middel van fisieke relief en kontras ‘n effek van ruimtelike diepte te bereik. In No.8 is dit asof Skotnes ‘n keerpunt bereik en die stilistiese oplossing in sig het. Die oplossing is grootliks gebaseer op ‘n meer oortuigende gebruik van ruimtelike en kleurperspektief. Die figure is nie meer in ‘n enkele vlak vasgeknel nie. Kleintjies staan agter en groteres voor om ruimtelike diepte aan te dui. Hulle is nou ook nie meer net liniere raamwerke nie, maar meer bevredigend opgebou deur middel van kleurkontraste. Hier is ook nog ‘n uit hout gesnyde figuur gemonteer, maar hier werk dit beter perspektief gebruik mee om die skerpheid daarvan meer aanvaarbaar te maak, aangesien die figuur illusioner nader aan die aanskouer staan as die ander. Daar is nog ‘n mate van ruimtelike en komposisionele onsekerheid in hierdie werk, maar dit verdwyn in die res van die skildrye. Kleurvlakke word by hulle omlynings subtiel vervaag om die indruk van linieriteit op die agtergrond te stoat. Die omgewing waarin die figure staan is nou met ‘n gesofistikeerde aanvoeling vir geskilderde ruimte aangetoon. Die invloed van die houtsnee is nog merkbaar in die abstrakte vereenvoudiging van die figure en die landskap, maar dit het nou ‘n positiewe uitwerking. Die vereenvoudiging laat nie die soliditeit van die figure verlore gaan nie, maar gee aan hulle ‘n gevoel van indrukwekkende monumentaliteit en terselfdertyd ook, soms, stille bewoenheid.

Johan Bruwer

Beeld, 17 March 1975

The precursor to the Visit to a Battle Site series is a painting entitled Independence, which Skotnes completed for Finans Bank on 2 January 1974. It is an arid, desolate landscape, but great gatherings of spectral populations are suggested within its rocks. A solitary figure, engraved upon a piece of wood, is superimposed on the painted surface. In response to the patron’s request, Skotnes explained how he had endeavoured to express independence in this work:

The original theme of ‘Independence’ was to me the independent man – man who, in spite of his environment, stands like a pylon. The use of the pylon theme throughout history was a symbol of fertility – intellectual fertility as well as physical fertility, for example the great hero figures who seem to grow out of their physical environment and yet somehow stand apart from it. They become the catalyst of their times in which all things, good and bad, are embodied. Hence when I constructed my painting I used a quite forbidding landscape and placed my pylon in the midst of it in a different material. Naturally the forms I used were in spirit, I think, African, and though it is a small touch I used stinkwood as my pylon as it is our most celebrated wood.58

The Visit to a Battle Site pictures which followed were created in a more contemplative mood and became more painterly and mystic as the series progressed. His interest in wood engraving and cutting is evident not only in the harshly delineated forms that define the plain and the horizon of the battlefield, but also in the wooden figures attached to the surfaces of the paintings.

Skotnes completed several pictures in this hybrid style. Then, while working on No.8, his dormant painterly intuition banished the graphic artist and woodcarver in favour of the painter. Even though a cut-out wooden figure is still attached to this picture, softly painted figures encroach upon it, and seem to threaten its place in the field. The hills on the horizon (which remained virtually untouched in the reworking) retain the delicate network of lines, but they are no longer as pronounced as in some of the other panels.

Having tasted this new freedom, and having discovered an evocativeness with the potential to communicate the mystic ambience he had experienced at the site, Skotnes turned to the completed panels that were awaiting exhibition. The first one he felt compelled to change, No.3, was, in fact, sold. But he was now so convinced of his new vision that he could not tolerate the original concept. He removed the attached carving and repainted the remaining figures entirely on a silvery grey background. Only a fragment of the hills on the horizon remained as it had been in the original version. He continued to rework the other paintings and to begin new ones: ‘They grew out of the picture [i.e. No.3] that is underneath your picture [i.e No. 9],’ he wrote to the owner, ‘that obliterated work was the key to the series.’59

No.2, underwent a similar change. The ‘new’ work (No.10) is now in the Pretoria Art Museum, while No.6 was repainted to become No. 11, now in the Sanlam Collection.

A few years after completing the Visit to a Battle Site series, Natal and the history of the Zulus were to call upon the artist yet again. In 1979 he was responsible for the decoration of the Ulundi Holiday Inn. He designed the wall hangings and made large incised paintings to embellish doors and the reception counter. On the wall dividing the dining area from the kitchen he made a decorative sgraffito mural featuring a still life and a huge cockerel. But the major work is a sgraffito mural in the conference room portraying the militant history of the Zulu people.

Consolidation and continuation